Xu Zhi Wen – Appreciating Traditional Chinese Ink Painting

Mr. Xu explained that traditional Chinese ink painting stems from China’s earliest recorded history, and uses many of the same techniques and subject matters in the present day. Maintaining ancient traditions are an important part of Chinese life and culture, as well as in art, which is one of the main reasons for the enduring popularity of black ink paintings in China today.

The absence of colour, perhaps for many westerners, may make the artwork seem a little bleak and devoid of life, but Xu Zhi Wen explained that black and white are seen in China as the two most primeval and basic colours of life, forming an intangible and essential component of ancient Chinese philosophy and science, as the two integral “colours” of their Yin and Yang symbol, representing the real and imagined, the empty and the full, and in art terms, the solid and the space, the outline and the shade.

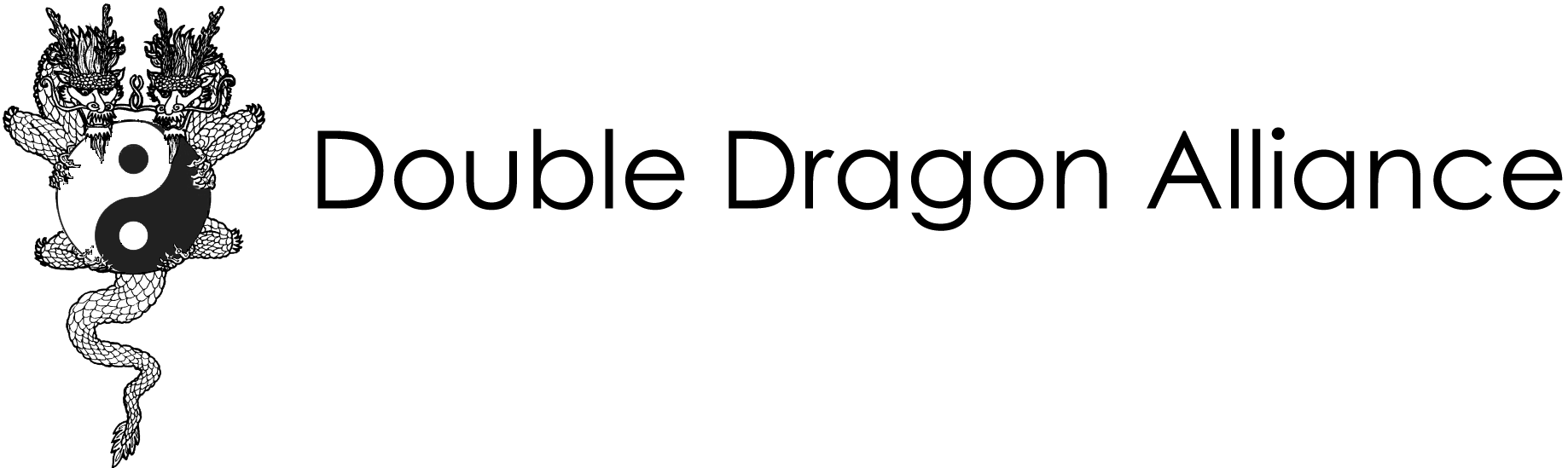

Black in Chinese art represents all other colours and tangibility, white stands for light, space, depth and intangibility. Although other colours are also to be found in Chinese art, coming into popularity around 3000 years or more ago; black and white ink paintings, (white is represented by the empty spaces found in the artwork) is still the most predominant form of painting in Chinese art.

The equipment for Chinese art is therefore slightly simplified, in terms of the palette of colours and hues required.

The artist needs black ink, which comes in several different grades and types, water and a parchment type of paper, often made of rice, bamboo or other material that has an absorbent quality. The artist tends to keep several bowls of water on hand, one clean, one very “inky” and one slightly ink-stained, to help build the necessary depth and perspective to the shading.

The brushes traditionally are made from a type of goat hair, or a kind of polecat found in China. There are several grades, thicknesses and types of firmness and softness of brush for different types of work or subject.

Beginners will usually start with a goat-hair brush of a firmer texture.

Most experienced artists will have a large array of brushes on hand, and once they have decided on the subject for the picture, prepare their ink whetstone for the liquid ink, (in ancient times ink would always have been prepared from an ink block, traditionally being ground with the right amount of water to create the required consistency) their bowls of water, then moisten and and squeeze out their brushes, ready to begin.

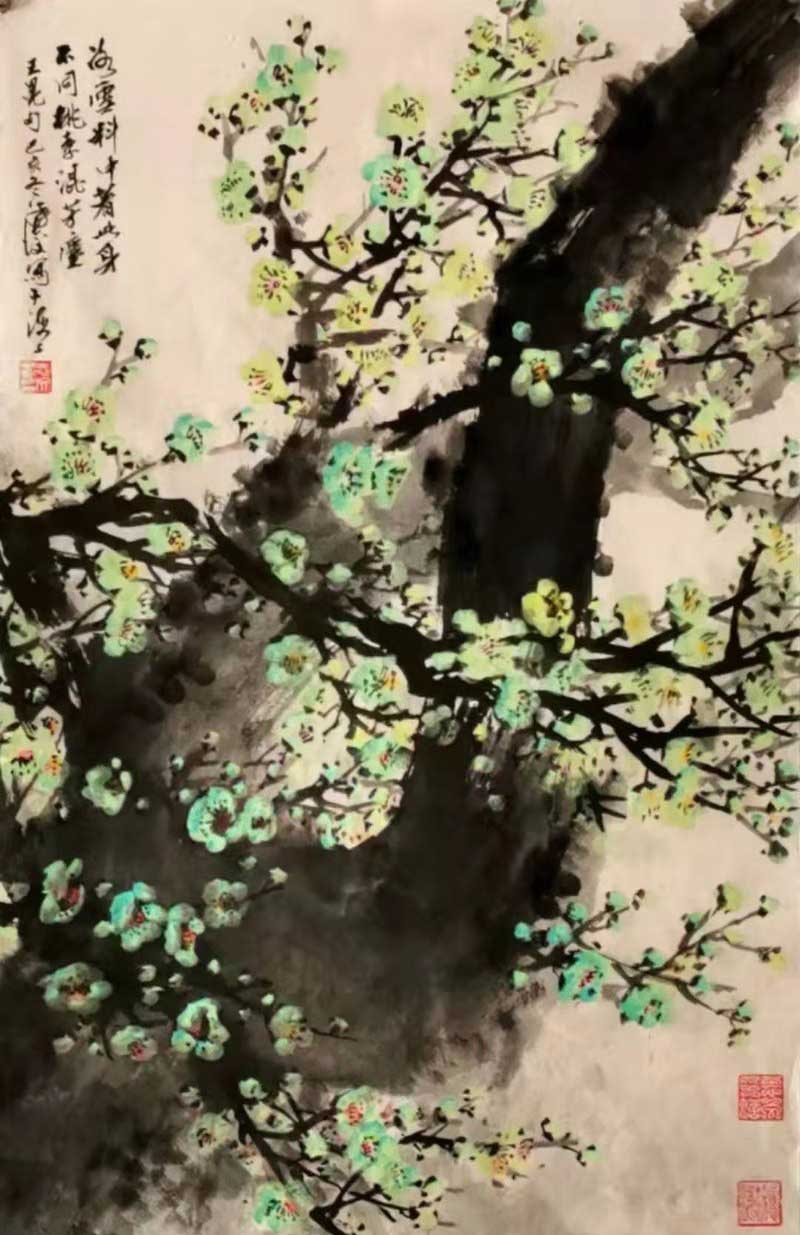

Chinese calligraphy (and then later Chinese ink painting) came into being based on prehistoric, cave paintings, rather like the early-man, cave paintings we also know of in the west. Earliest forms of calligraphy over 4500 thousand years ago, were pictorial, rather than the characters we see in Chinese writing today and were simplified images of what early-man saw. Traditional Chinese artists and writers have used the same methods over the ages, but their images and pictures have evolved to be not only beautiful pieces of artwork, but also used to purvey provocative, political messages, representing ancient, pictorial idioms that criticized emperors, government and officials, all under the guise of celebrating aesthetics and pleasing the onlookers. A common theme was pictures featuring birds, fixing a critical eye on the observer, or caustically looking up at the sky, to represent an old Chinese proverb about casting aspersions on the powers above.

Thus, ancient Chinese artists through their art practised the old English saying “The pen is mightier than the sword”.

Mr. Xu, who is now in his 70’s, began painting in his early childhood. Coming from a very poor family, he couldn’t afford paper to draw on, so started painting and drawing on any material he could find, including wood, his father’s cigarette papers, flooring and walls among other things, in fact he was an early proponent of graffiti in China!

Fortunate to find a benefactor in his youth, who admired his prowess, he began studying in a “vocational” art college, receiving excellent tuition from some high level and well-known artists of their day, who would offer classes at the college in Shanghai. Following his graduation, he was invited to the USA to work and teach at a university there.

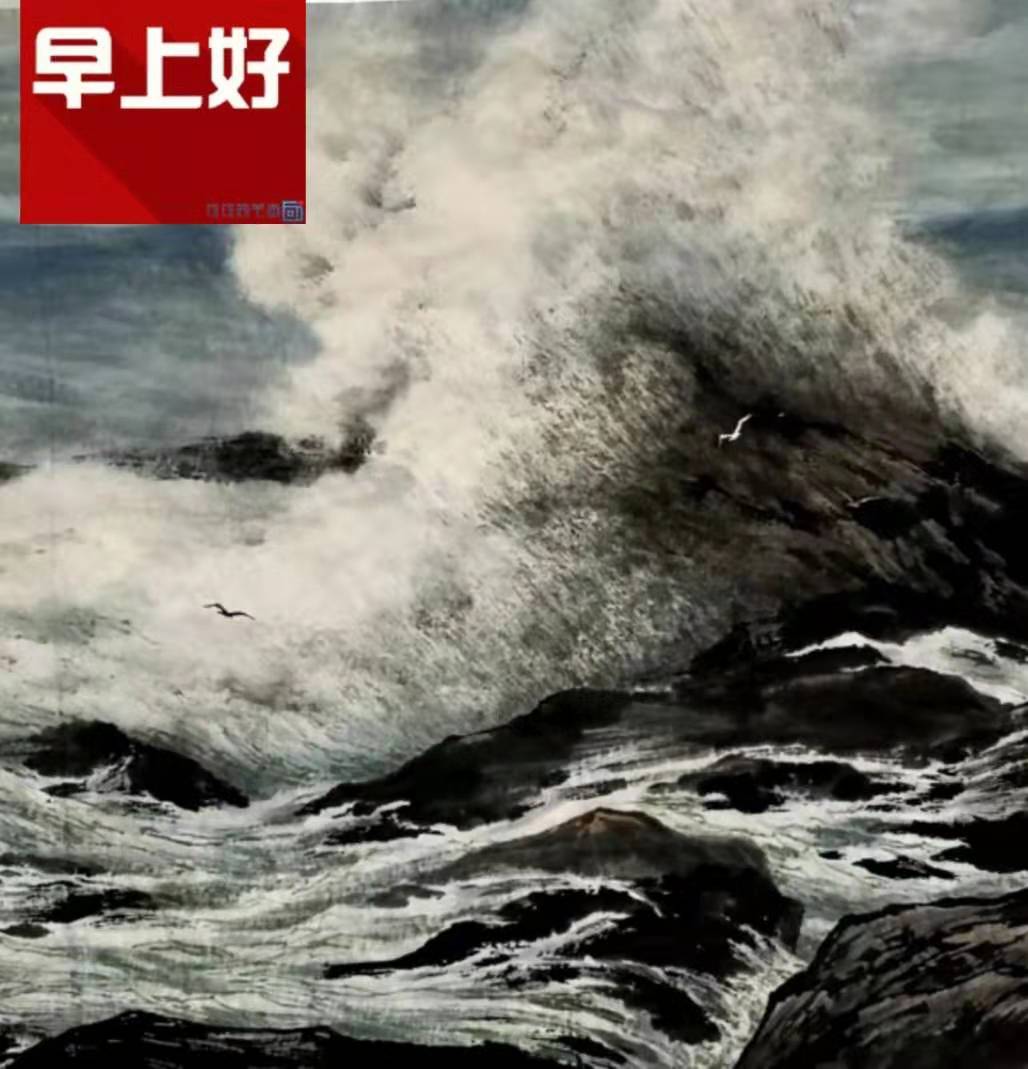

While in the USA, he began to notice the different styles of western art, the various mediums, the use of colour and brushwork, plus the different “feel” of the artists’ styles; especially the expansive and open way of depicting life or nature, infusing the artwork with a sense of freedom, energy and imagination. He concluded that in comparison to Chinese painting, western styles of art were more complex and to help Chinese painting evolve and garner a new audience’s appreciation, he would try to incorporate some of these ideas to enhance his own work. He started to encompass the freestyle brush techniques in his own paintings, progressing to large murals and canvasses, slowly gaining recognition for mountain and water scenes, in particular capturing the essence and expansiveness of the great oceans.

Now, back in Shanghai Mr. Xu is eager to introduce Chinese ink painting to a wider audience, both abroad and in China, and hopefully further develop traditional Chinese ink painting as a form of art that can be appreciated both for its delicate intricacy and refinement, as well as its energy and power.

To begin any painting, there are several rituals before the artist commences.

In Chinese ink painting, this includes the preparation of the ink, water and brushes, a kind of meditation if you like, to put the artist in the right frame of mind, before creating the image on the paper.

The paper is always laid on a type of thick felt mat, which also helps to blot and absorb the ink and water, allowing it to dry quicker and provides a flat, firm, yet soft surface to paint on, as Chinese artists don’t use easels, always painting on a horizontal surface.

The brush is first immersed in clean water, to moisten it, dipped into the ink, then immediately dipped back into the water to dilute the ink slightly, then blotted on tissue or the felt mat, to dry off the excess liquid.

When the brush is first applied to the paper, if the brush is too wet, the paper, despite being absorbent, will become soggy and possibly tear.

The artist, with experience, will gradually be able to recognize how much ink and water is generally necessary and how much is required for each individual subject.

When Mr. Xu is painting mountain and rock scenery, he uses larger brushes, which are kept quite dry, after being dipped and rolled in the ink and then well blotted first, before being applied to the paper.

The amount of ink on the brush, according to the way the brush is rolled and stroked in the ink, varies from the base to the tip; thus giving varying depths of colour and boldness to the picture, which also helps to build up the sense of space, dimension, shading and perspective.

The brush also has different stages of wetness running its length, with the tip being wetter and the sides and base quite dry.

Cliffs, mountains and rocks use larger, bolder strokes, due to the ragged nature of the kind of rock-faces found in Chinese topography, made in quite a frenetic and free way, letting the “dry” ink on the brush be wiped and rubbed onto the paper, rather than “painted” on.

The brush is used on the paper in differing directions and stroke methods to build up the rocks and mountain crags, with the “white” empty spaces emphasizing the depth perception and shading of the rock-face. In Chinese terms they will say it is creating the sense of “Yin and Yang” or empty and full in harmony, bringing 3 dimensional life to the picture.

The different types of water being used are also another way to build up space and depth; the control of the brush dipped in the ink and the different “colours” of water are integral to the whole process of diffusing the ink and letting it leach onto the paper naturally, rather than simply just painting the colour on.

Once the actual picture is finished, the painting itself has one further step in order to be completed.

In Chinese art, there is always a space left at one of the sides for the artist to complete the picture with some calligraphy; usually a poem or saying that will compliment the painting, plus the date, time and name of the artist.

The painting will also be stamped, usually twice with the artist’s personal seals which have his name carved into them.

The idea of this is also to provide balance to the painting, again adhering to the principle of Yin and Yang, creating a sense of equilibrium of words and pictures to create totality.

Xu Zhi Wen said that for beginners, the biggest challenges are choosing the right brushes and type of paper. To begin, they should go with lower quality paper, one that is forgiving of poor techniques and water/ink usage, as beginners cannot properly control the amount of water and ink applied to the brush and will tend to make it either too wet and thus over-soak the paper, splodging the colour, or alternatively keep it too dry, which prevents the ink “entering into” the paper and becoming one with it; so the subject doesn’t look life-like or part of the paper, rather the colour just sits on the paper, a bit like a transfer. Sometimes, the contact of the brush on the paper maybe too heavy and the subject will be blotted and have no definition or form.

If the painting is going to be a large one, the painter shouldn’t focus on the size, because if they view the “canvas” as if it’s large, they will be overawed by the size and subject, and have no direction. Instead they should think of a large picture as a small one, and a small picture as a large one; this way, they will not lose sight of their aim and can express their feelings, without being overwhelmed or constricted.

In short, the “secret” Mr. Xu explained is lots of practice and experimentation, to enjoy playing with the materials and finding your own way to express your own style.

To truly appreciate the art form, which is still perhaps somewhat unknown in the west, one needs to know something about Chinese culture and philosophy. The integration of art, calligraphy, movement and meditative practice are all components in the search for self-cultivation that is an important fabric of Chinese life.

For many painters throughout the world, painting is a way not just to earn a living, or wile away the hours, but is also a form of meditation, a way to find inner peace and tranquility.

Chinese ink painting has existed over thousands of years, but like any art mode needs to grow and change in order to develop further and allow new audiences to appreciate its artistic qualities and potential for creativity.

Mr. Xu Zhi Wen hopes Chinese ink painting will gain popularity among western artists, who he believes can find new ways to interpret their ideas in the Chinese ink painting medium.

Article by Rose Oliver MBE, from an interview with Xu Zhi Wen