Playing the Form – The Metamorphosis of Practice

Story by Rose Oliver M.B.E

During the many stages of our training and practice life, we will meet a range of problems and questions related to the form.

As beginners, we need to know the exact physical and structural movements, including the placement of hands, feet, head etc, in order to correctly align the body for the optimum utilization and flow of energy, as well as to understand the basic premise of each technique.

Here the form resembles sketching the outlines of a picture or the foundations of an architectural design. Without this A, B, C of rather diagrammatic learning, similar to painting by numbers, we would be in danger of just executing a mish-mash of jumbled movements, not the correct sequence of applicatory techniques and certainly with no clear direction or intention in our postures.

Cultivating Gongfu

After this first stage of learning, which includes understanding the exact nature of the moves, a process which can take one to three years to complete; students start to work on cultivating and deepening their “Gongfu – 功夫”.

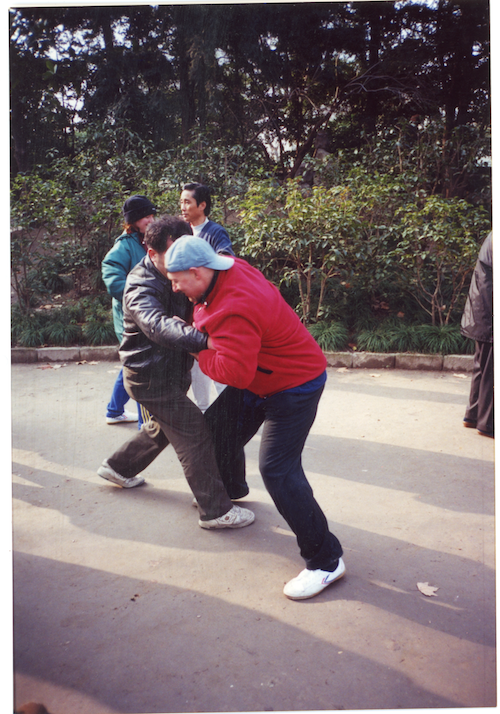

At this point, it’s very important that a student trains with a master who is able to also demonstrate and lead the student through these vigorous, demanding and athletic moves, in order for the student to successfully open their bodies and meet the high requirements of each individual posture and reconfigure their bones, joints, sinews and energy to be able to integrate every part of their body into a unified whole when executing the techniques.

At the same time, the student is learning how to utilize and control their natural body mass and body weight, (gong li – 功力) in addition to timing the release of this combined power in perfect unison with the flow and transition of their own and their opponent’s movements.

Changing Methods

When passing through this stage of the students’ learning, the teacher is also very much physically involved, leading and guiding the student through many repetitions of each movement, testing postures, demonstrating power and release and applications, plus allowing the student to try out the techniques on the teacher too, so as to assess correct usage or identify potential problems.

Traditionally, teachers at this stage of a students’ training, would optimally be in their late 40’s to mid-60’s; as at this age, teachers are still in a physical state where they can sink down effortlessly into deep postures and expend the amount of effort and energy necessary to carry the students through the rigours of such physical work.

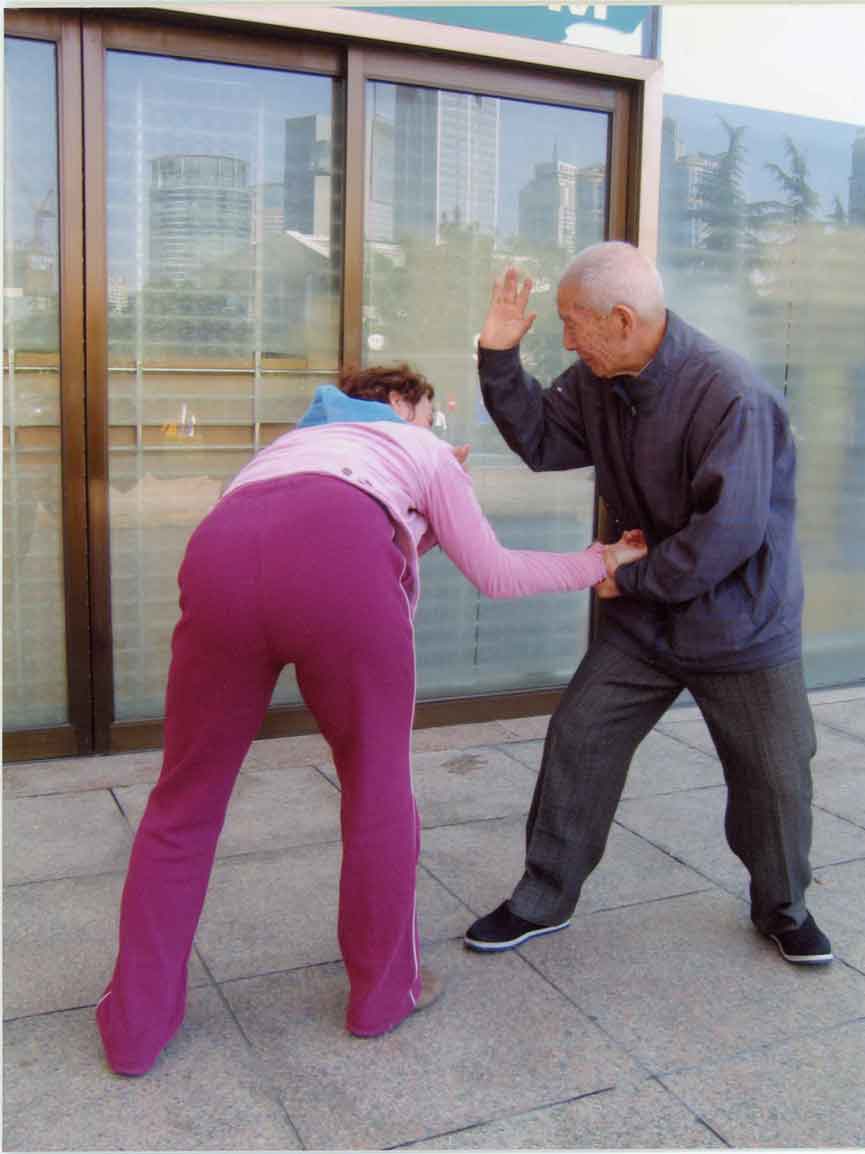

As teachers reach their 70’s and beyond, their Gongfu level of course surpasses those earlier years of training and they are no longer constrained by the physical body; able to utilize the energy, intention and spirit when executing their moves. In fact, their movements become natural, no longer a series of studied postures or techniques, rather a natural extension of coordinated applicatory moves, which seem inseparable from those normal daily movements, used when brushing the hair or washing the hands.

Internal Arts

When the teacher plays the form at this stage of their training, they no longer need to sink into deep postures or make such outwardly expansive or powerful moves; everything appears soft, fluid and continuous. The form at this level resembles painting light brush strokes onto the paper, where the painting effortlessly conjures up a picture using minimum strokes and the use of “empty spaces” to create shapes. In Chinese they call this Hua Quan – 化拳, “Free painting form practice or dissolved form practice”.

Everything happens internally and there no longer needs to be a visible release or gathering of power; the soft continuum of movements appears to simply “wrap up” and entangle a student’s attack in push hands or sparring, in a seamless fashion.

This is an important stage in a teacher’s martial development and in their cultivation of energy and health. Without which, if a master continued to regularly expend energy and physical output, he would quickly deplete his energy stores and “original qi/pre-natal energy- 元气”, affecting his health and longevity. But what happens when a student starts to learn from a teacher at this particular stage of the teacher’s development?

Understanding the concept of relaxed in Taiji

The soft, almost “floppy” relaxation of the teacher can be misinterpreted by beginning level students, who seek to emulate the same ‘noodle-like’ softness of the master. The forms these students perform, devoid of the years of ‘Gongfu’ training, internal work and sheer hard graft put in by the masters, instead may resemble a soft, flimsy, almost zombie-like string of moves, lacking life, energy, spirit or substance.

During push hands for example, they are quickly ripped out of their root and tossed around like a rag-doll, unable to combat an opponent’s strength or power. This is neither the fault of the student, nor the teacher, just an unfortunate consequence that may exist when students haven’t yet fully grasped the concepts and sensations of internal work, or where language barriers prevent a teacher from properly communicating with the student.

In traditional Chinese training circles, the antidote to that type of situation lies in the martial family itself.

Many masters at this stage of their own development have already trained a number of senior students, who will now take over the mantle of ‘manual labour’, of teaching the beginners or intermediate students, allowing the master to focus on correcting individual moves or problems encountered, both by the beginners and by the ‘elder brothers or sisters’ during the teaching process; if the beginners are only taught by the elder siblings, without the master’s advice or corrections, they will never progress beyond this early physical stage, as they will not have experienced what higher-levels of softness and relaxation or subtle inter-plays of internal energy changes feel like. So the master is ultimately responsible for the learning of the beginners and intermediates, in addition to helping refine and hone the advanced students’ skills and passing on the finer points of ‘gongfu’ mastery.

Tutoring as a System

In fact, this tutoring system correlates to the way a family works, with elder brothers and sisters taking care of the younger siblings and taking some of the pressure off the parents, (or in this case the master) as they grow older, whilst the parents still retain overall control and care of the family, which becomes less physical, but more mental or spiritual guidance over the years.

Our bodies, whether they be those of a great martial arts master or someone just on the outset of their training are still governed by the rules of nature and its physical laws. This is not to say that older masters cannot still execute deep postures or exhibit great power.

When I began to study with Master Dong Bin, he was already in his 80’s, but he was still able to demonstrate powerful moves and deep, low stances, plus perform some of the more vigorous and demanding leg training exercises that his own teacher, Master Dong Shi Zuo had taught him when he was a young practitioner; as well as throwing us all around in push hands. Rather the master must be more sparing in giving these demonstrations, or performing such moves; just like someone on a monetary budget, they must know how much money they can spend and when to conserve their funds.

Listening Energy

Whilst of course great masters can always produce miraculous displays of skill that defy our belief and dazzle us with their ease and finite control, they cannot remain a ‘hod-carrier’ from the beginning of their practice or teaching career to the end; they must adapt their own training, practice and teaching according to what their body tells them.

Listening energy or “Ting Jing 听劲”, is not only confined to ‘hearing’ what your opponent’s body or energy is doing in push hands for instance, it’s also listening to yourself. Not merely though in relation to a push hands or sparring situation, but also in terms of one’s health, physical changes and subtle variations in everyday reactions and feelings.

Martial arts practice, including Taiji is very much concerned with the practitioner’s health, as well as self defence, knowing our bodies and how to handle, treasure and work them to their optimum level will result in better practice, better Gongfu and better health.

Many masters, as well as ordinary people have suddenly found themselves caught unexpectedly by illnesses or conditions, which perhaps may have been recognized much earlier, if they had learned to understand themselves or listen to their bodies better and perhaps then modified habits or training accordingly.

Understanding One’s Body

Following the natural progression through a training regime means learning the basic foundation exercises, pushing ourselves to reach the full range of movement and opening our bodies, but as we grow older and as our training proceeds, we need to guide our bodies through what will help them maintain good health and longevity, as well as attain martial ability.

Understanding this phase in our teacher’s training lives, as well as our own, will also help serious students wishing to focus on martial skills, work with a teacher that can really guide them along this physical path and later help them into the next higher stages of energy work.

The Concept of Yin – Yang

The Chinese concept of “Yin and Yang 阴阳” is an ever-changing, complimentary, living entity – not just written words in a book or vague esoteric concepts.

Working with a master who can transcend a static, one dimensional view of these ancient concepts and who can guide a student through their whole ”training life”, requires great skill, effort, knowledge and energy, and many times needs the combined work of a whole, extended martial family to successfully nurture and cultivate the next generation of martial artists.

Seeking Balance

Understanding how our teachers develop and at what stage they are at in their own development, prepares us for the complex training road ahead, allowing us to hone our skills, keep healthy, be a credit to our masters and systems, as well as be able to help others. As in so much of Chinese culture, the underlying thread that runs though the whole society, not just in their martial arts, is one of balance.

Through its constant pursuit and by making minor adjustments along the way to maintain it, the Chinese feel one can achieve great skill, good health and harmony with oneself, the society and one’s environment; something that as Taiji practitioners we all hope to achieve.

Balancing ourselves within our practice and in relation to our bodily and spiritual health is the first step.